Crime: 1980s, 1990s,

Crime: 1980s, 1990s,  Crime state:

California,

Crime state:

California,

LDS positions: Stake presidency counselor, Stake president, Sunday school,

LDS positions: Stake presidency counselor, Stake president, Sunday school,  During crime: Stake presidency counselor, Stake president,

During crime: Stake presidency counselor, Stake president, - LDS mission:

unknown

unknown  Alleged:

10 or more victims, Multiple victims,

Alleged:

10 or more victims, Multiple victims,  Alleged crime scenes:

Perpetrator's workplace,

Alleged crime scenes:

Perpetrator's workplace,  Criminal case(s): Convicted, Jury trial, Overturned/reversed, Prison,

Criminal case(s): Convicted, Jury trial, Overturned/reversed, Prison,  Alleged failure to report

Alleged failure to report- AKA John E. Parkinson

updated Sep 27, 2025 - request update | add info

updated Sep 27, 2025 - request update | add info

This case took place in Fairfield, California and was filed in Solano County Superior Court.

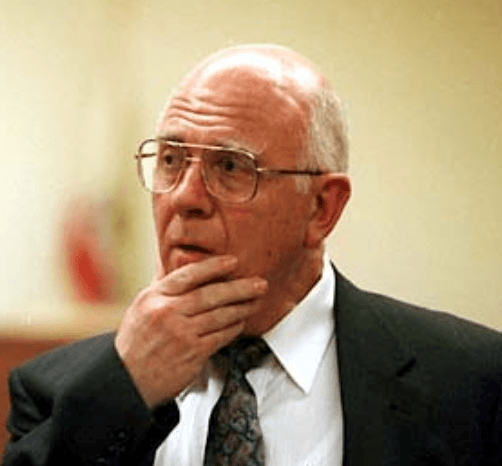

John Parkinson was a Mormon stake president in California from 1981 to 1991 who allegedly used his position of trust as a doctor and religious leader to molest and misdiagnose women and children who attended the Mormon church.

A female member became concerned about his care and collected accounts of his abuse and brought them to the Mormon leadership. He was allegedly protected by the Church higher authorities and this woman moved away, allegdly branded as a troublemaker. This allegedly allowed him free reign among the membership and it took years to get his license to practice medicine removed.

His license was removed in part for diagnosing women with cancer, prescribing chemotherapy, and then claiming he cured them when they did not have cancer in the first place.

He continued to practice medicine and was later found guilty of practicing medicine without a license and other crimes related to the earlier allegations.

In 2003, Parkinson’s criminal conviction was reversed.

Have any info on this or other Mormon sex abuse cases? Contact us.

As an independent newsroom, FLOODLIT relies on your generous support to make thousands of reports of sexual abuse in the Mormon church available. If you find our work helpful, please consider donating! Thank you so much for helping us shine a light.

Sources

- Former doctor, stake president faces sex-abuse, drug charges,

- Former doctor to remain free on bail,

- The Fairfield Wives,

- Doctor Ordered To Prison in Molest Case / Charges brought by 2 female patients,

- Solano County court records search 1,

-

1. Former doctor, stake president faces sex-abuse, drug charges

A former physician and LDS stake president faces multiple charges of molesting two former patients and practicing medicine without a license.

Trial opened this week for John E. Parkinson, a former oncologist who was stripped of his license by the state Medical Board nearly two years ago for performing excessive pelvic exams. He was once a cause celebre, with more than 100 supporters attending his Medical Board hearings and wearing green ribbons of solidarity.

But this week, Parkinson, a father of nine, sat alone in the courtroom or with just one or two of his children as a jury was selected.

The 38-year-old [FLOODLIT note: this is incorrect; he was 58] former doctor faces 23 counts of sexual assault, 10 of violating drug laws and two of practicing medicine without a license. He has pleaded not guilty, and his trial is expected to last four to five weeks.

In early 1993, the board began investigating the complaints of a former patient who said the doctor had performed sometimes daily pelvic exams on her for nearly 12 years.

That case prompted 28 more women to come forward with similar stories. Fifteen sued for malpractice, all reaching undisclosed financial settlements with Parkinson's insurance company.

Police say that after losing his medical license, Parkinson continued to treat a mother and daughter from Vacaville who were fellow church members and family friends.

Police testified that the women came forward after Parkinson told the daughter during a pelvic exam he loved her and wanted to marry her. The women are not being identified.

Parkinson was arrested on Aug. 18, 1995. When police searched his home, they found "virtually every room was filled with controlled substances, garbage, food and syringes," wrote then-Solano County Deputy District Attorney Anne-Marie Schubert.

-

2. Former doctor to remain free on bail

A former physician and Mormon stake president in Solano County will remain free on bail pending an appeal of his sentence for allegedly sexually assaulting two female patients.

John Parkinson, the 66-year-old former president of the Fairfield Stake of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was sentenced Monday to six years and eight months in prison.

He remains free on $300,000 bail until an appeal alleging juror misconduct is heard.

Parkinson's attorneys say a female juror who works as a nurse improperly used her medical experience to contradict Parkinson's testimony during deliberations.

-

3. The Fairfield Wives

Fairfield, California, is situated between the San Francisco Bay and the Central Valley in such a way that a near-constant warm breeze blows through on summer days. It's as if a giant hair dryer, set on low, were pointed at the city, the hub of Solano County. The breeze is part of what the Chamber of Commerce calls Fairfield's mild climate. The Chamber is also quick to point out that Solano County is the fastest-growing among Bay Area counties. Fairfield once was nothing more than a drive-through town between San Francisco and Sacramento. Now, thanks to skyrocketing home prices closer to the bay, Fairfield has truly become a “bedroom community” — which means that thousands of its residents get up every morning and head west on I-80 into an amazing traffic jam, and that the Fairfield schools are painfully overcrowded.

The central point of recent Fairfield history is the advent of Solano Mall. People tend to say things happened either before or after “they built the mall.” That's about the time when folks started coming from the south to live here.

But if the construction of a shopping center and an influx of suburbanites have changed things a little in Solano County, the change has not been fundamental. Fairfield remains a near-caricature of Middle America, a town so quaintly suburban that it has an almost surreal, Stepford-esque, David Lynch feel to it. Downtown is stubbornly planted in yesteryear and looks like Main Street U.S.A. Streetlamps line the sidewalks. Ladies in floral dresses and short pumps carry birthday cake to county office buildings. A large, blue arch hangs over one street, announcing, in letters that light up at night, that you have entered Fairfield, the seat of Solano County.

There's a farmers market every Thursday beneath the arch. In fact, there's nearly always some kind of community event going on somewhere in Fairfield. Travis Air Force Base, which is located within the city limits, has

1/35definitely left its mark, which includes a growing contingent of current and retired military personnel. People who live here tend to be conservative. A lot of mothers stay home to raise their children.

Fairfield is home to a large Mormon community, and for a long time many of the town's civic leaders have also been local leaders in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Until the recent disclosures that have so disturbed the harmony of this serene and proper town, Dr. John Parkinson was one such leader.

Sitting in the immaculate living room of her immaculate house in Granite Bay — an affluent suburb north of Sacramento near Folsom Lake — Kem Atkinson sips lemonade and relives a time when Dr. Parkinson played an enormous role in her life. Age has been kind to Atkinson. She remains the same thin, energetic, attractive woman she was years ago in Fairfield, although the blond hair has turned ashen and glasses cover a face that wears more wisdom than it used to.

“I've never met anything quite like Fairfield,” Atkinson says. She interrupts herself every so often to attend to the periodic crises of her 4-year-old grandson, who has lost an action figure or his swimming trunks, or just needs some attention. Nonetheless, she is very clear on the issue at hand, something she has given sworn testimony about. Her story goes like this:

Kem Atkinson's problems with Dr. John Parkinson began two decades ago. She was 28 years old and the mother of three children, all under the age of 6. She and her husband had moved to Solano County when he got a job in sales at a drug company. Fairfield was the center of Atkinson's territory, and Parkinson was an important client. The doctor had a big practice and served on several committees at the local hospital.

The Atkinsons were also active in the Mormon Church. Most of their friends and neighbors were Mormon, too. Their social life revolved around church activities: dinners, dances, fireside talks, kids activities, Sunday

2/35school, and so forth. It was quite possible to spend every day or evening involved in church activities, not to mention three hours at church on Sunday and monthly trips to the Mormon temple in Oakland.

None of the devotion to church life was new to Atkinson. She had grown up in Montana, gone to the Mormon-affiliated Brigham Young University in Utah, and married a young Mormon man just returning from a mission. They set about bearing and raising children immediately and, of course, Atkinson devoted her life to her family.

In late 1977, Atkinson began to be plagued with cramps and diarrhea that seemed to last for weeks. A sister in the church suggested that Atkinson go see Dr. Parkinson. Atkinson did not have a regular doctor at the time, nor did she and her husband have any extra money. She didn't know Parkinson, but she certainly knew who he was: a well-known doctor, first counselor to the local stake president in the Mormon Church, a highly revered man. Going to see Parkinson made all the sense in the world.

Parkinson examined Atkinson and sent her almost immediately to the hospital for a series of painful rectal probes.

“I was like a beetle with my rear end up in the air,” she recalls.

Parkinson also prescribed low-grade antibiotics, which he had Atkinson take for more than a year. And the doctor directed Atkinson to come for office visits at least three times a week. Each time, he had her climb up on the examining table, feet in stirrups, while he put his fingers inside her vagina to perform a pelvic exam. Sometimes he'd have her squeeze his fingers and told her she needed to do more such Kegel exercises to tighten up her muscles. Sometimes he said that she had a yeast infection, for which he'd insert cream into, and rub around, her vagina. (Parkinson never gave Atkinson a prescription, so she could apply the cream at home.) [page]

Afterward, Atkinson would get dressed and walk into Parkinson's office, which was so cluttered with magazines and medical journals and papers and whatnot that she'd have to clear a path to a chair. On the way, she

3/35could see Parkinson in a dark, laboratory-type room, looking through a microscope. He would join Atkinson in his office, lean across the desk, and tell her, gently and sincerely, that she was very sick. She had inflammatory cells, he would say.

The doctor assured her that he would take her under his wing and make her well. And he would accept whatever her insurance would pay. But she had to continue to see him regularly.

“I was convinced he was my only hope,” she explains. “I trusted him because he was a member of the church, and he knew I wanted to get well so that I could have another child.”

As the weeks went on, Atkinson continued to take the antibiotics, along with some other medications Parkinson prescribed. She was cramped and plugged and in terrible pain. Often, she would be up for two or three hours at night, either pacing or sitting on the toilet.

“At one point, I was shaking, it hurt so bad. Nothing could come out of my body,” she says. “I remember laying in bed one night imagining that I could reach up and touch God's hand.”

Atkinson became increasingly nervous about leaving the house. She started looking at her watch from the moment she sat down in a temple ceremony — a highly sacred event that generally lasts about two hours — and often had to walk out amid the questioning looks of her sisters and brothers in the church.

People began to talk.

Among other reasons, people talked because Atkinson solicited advice from almost anyone who would listen. She brought it up at women's group meetings and potlucks. She talked to other women on the phone. Had they ever had anything like this?

“People would say little things like, 'Yeah, it's a lot of stress with three kids,' like I was crazy, or a hypochondriac, or something.”

4/35Eventually, Atkinson called a church member who was a nurse, and who asked Atkinson a lot of questions about Parkinson's procedure. The nurse didn't like what she heard. She told Atkinson to see another doctor. But Atkinson defended Parkinson. The nurse, she reasoned, must not understand what Parkinson was doing.

Meanwhile, the frequent visits to the doctor's office were becoming impossible to manage. Atkinson would usually go see Parkinson in the morning, when her husband could come home and stay with the kids. It was a constant juggle. But the ladies who worked in Parkinson's office were bulldogs. The doctor was very concerned about her, the ladies, who were also church members, would say. She needed to come in for treatment.

“I had three little kids and a husband,” she remembers. “He was new at his job, and we were so poor. I just couldn't keep this up.”

Finally, Atkinson couldn't take any more. She just stopped everything — stopped taking the medicine, stopped going to appointments with the doctor. That's when she started feeling better.

Soon afterward, Atkinson ran into Parkinson at a church event, and he told her that he was very worried about her, that she needed to come back in. Atkinson replied that she was going to take vitamins and trust in God to heal her. Parkinson reiterated that she needed to return for treatment.

And, she did. But not the way Parkinson had in mind.

By now, Atkinson felt better and the nurse's comments about Parkinson were continuing to play in the back of her mind. She and her husband had become suspicious. It was time for second, even third, opinions.

So, Atkinson arranged to see Parkinson one morning in his office, where he performed a pelvic exam, and again told her that she was very ill with inflammatory cells and needed to come back in two days. The same afternoon, she went to a specialist, who told her, essentially, there was nothing wrong with her that staying away from the doctor and off the medications he was giving her wouldn't cure.

5/35Again, Atkinson went to Parkinson, and again he performed a pelvic exam, telling her about the inflammatory cells and so on. The second afternoon, Atkinson went to a third doctor. Not only did this doctor tell her that she was healthy, he began to question why she wanted to be examined twice in one day.

Atkinson never went to see Parkin-son again.

Instead, she called the Medical Board of California and left a message on the complaint line. Then she made an appointment with B. Gale Wilson, one of the most powerful men in Fairfield. At the time, Wilson was stake president, the highest-ranking local official in the Mormon Church. He was also Fairfield's city manager, and had been for years. A street in town bears his name.

It was the first time Atkinson had ever gone to the stake president with a problem. He ushered her into an office in the church building, very formal looking, like it could easily be in a downtown law firm. Atkinson took a seat in one of the two or three chairs set ready for those who come to confer on matters of the soul and the world. Wilson sat behind a desk. Atkinson shared her concerns about Dr. Parkinson.

Wilson is unavailable to discuss what happened inside the office. Atkinson says he told her he would take care of things with Parkinson, and asked her not to report it to the medical board.

“He [Wilson] said, 'It will never happen again. Don't file anything. It would embarrass the church,' ” Atkinson recalls.

The instructions were easy to follow. The Medical Board's investigator didn't call back to follow up on the matter for weeks. When he did call, Atkinson simply said she didn't want to pursue a complaint. [page]

It wasn't over.

As time passed in Fairfield, Atkinson's husband was called into various positions in the church. By now, he was one of the bishop's two

6/35counselors. Some time after Atkinson stopped seeing Parkinson, she was talking with a neighbor friend, who was pregnant and had a sore throat. She said the bishop had sent her to see Dr. Parkinson.

“Parkinson had her up in the stirrups,” Atkinson said. “I didn't want anything to happen to her baby.”

Atkinson went to see the bishop, who also lived in her neighborhood, and told him her story about Parkinson. He was stunned. That night, the doctor called her house. Parkinson, she remembers, told them in no uncertain terms that he would not stand for her running around town making these accusations, that he could sue them, and that their church membership might be in jeopardy if she did not stop talking about him. (In court, Parkinson has repeatedly denied ever threatening anyone's church membership.)

Shortly thereafter, the bishop was at their door.

“I could tell he was scared,” Atkinson remembers. “He said he'd gotten a phone call, and that we were just going to drop it.”

In 1981, John Parkinson replaced Wilson as stake president in Fairfield. Kem Atkinson's husband was relieved of his calling in the bishopric. The Atkinsons continued to be active in the church, but it wasn't quite the same. There were idle comments and joking references about Kem Atkinson being the town maverick. No one came to help them when they moved to another house in Fairfield. They slowly became invisible.

“My home teacher [a church officer who gives family guidance] told me that the Lord was unhappy with me because I was speaking evil against the Lord's anointed,” Atkinson remembers.

A couple of years later, after another job transfer, the Atkinson family moved to Indiana. From there, they moved to Granite Bay. Kem Atkinson never was involved with John Parkinson again, until the afternoon, many years later, that an investigator for the Medical Board of California called to ask her a few questions about the doctor in Fairfield.

7/35Through his attorney, Parkinson refused to be interviewed for this story. But public records provide some background information about him: Parkinson was raised in Idaho, the son of divorced parents who each remarried, giving their son an extended family that included five siblings. He graduated from the University of Utah in 1956, and continued there to complete medical school. Parkinson had wanted to be a doctor for as long as he could remember.

After medical school, Parkinson entered the United States Air Force as a captain, and was stationed at Travis Air Force Base in Fairfield. Four years later, he left the Air Force, but not Fairfield. For one reason or another, a burgeoning group of Mormon professionals was beginning to build a community there.

Parkinson set up his practice in 1962. By then he and his wife, MaryLynn, had already started a family that would grow to include nine children and three foster children. Tragedy struck that same year, when Parkinson's 5- year-old son died of cancer. Two other sons suffered from schizophrenia.

Parkinson's practice grew with the town. He and a handful of others, like his good friend and officemate Louis Madsen Jr., a dentist who'd also come out of Travis, became unofficial city fathers, leaders in church and community.

They invested both financially and socially in the development of Solano County, and reaped great reward. After three decades, virtually everyone in Fairfield knew John Parkinson in some way or another. Most knew him as a quiet, pudgy, balding man who was generous with his time and kind to people in need. He seemed to treat every patient who came his way. He rose to stake president — the highest local position in the church — and served for a decade, before stepping down in 1991.

It is considered an honor to be called into service in the Mormon Church. Church leaders, who members believe are inspired by God in their selections, directly call people to positions at the level of bishop and

8/35higher. Those who have been so called are looked upon as possessing particular wisdom and high moral character by members of the church community.

Members turn to those church leaders for both spiritual and temporal needs. From its vast coffers (faithful members give one-tenth of their income to the church), the church provides support — money, food, clothing, and almost any type of service — to members in need.

Even after he left his post as stake president, Parkinson continued to teach Sunday school. Many considered him a scriptural scholar. Church members turned to Parkinson for spiritual help, advice and leadership, and medical treatment and counsel, all of which he gave them in a convincing and authoritative way.

The Mormon Church is structured into geographic groupings headed by lay ministers. These ministers have no seminary-type education, and they don't get paid. In fact, church leaders hold secular jobs while they minister to their flocks. Church members are clustered in wards (similar to Catholic parishes), each led by a bishop and two assistants known as counselors. Several wards comprise a stake, and each stake is headed by a stake president and two counselors.

Geraldine Rasmussen and her husband Paul raised horses on a patch of land near the small town of Dixon, and were active in the Mormon Church, where Geraldine occasionally taught Sunday school and participated in

the activities of the Relief Society, a women's organization. Dixon is not nearly so grand as its citified cousin, Fairfield. Dixon's only real landmark is the Milk Farm, an ancient restaurant along the side of the highway, where a neon cow jumps over a moon and waves its tail at weary drivers. There is little else in Dixon besides the orchards and fields that surround the area's ranch homes, which range from well-kept to downright dilapidated. [page]

9/35The Rasmussens initially became concerned about Dr. Parkinson in an indirect way. They rented a second home to Geraldine's sister, Anne Aldrich, whom everyone in the family called “Annie” and who was the single mother of a 7-year-old son. In the early 1990s, Rasmussen and her brother, Chance Williams, became concerned about Aldrich. She seemed tired, lethargic, ill, even though she was seeing Parkinson for a variety of ailments with increasing frequency. In fact, Rasmussen and Williams claim Aldrich was seeing Parkinson as often as twice a day, and that he would sometimes come to her house.

“We felt that she ought to get a second opinion. That the relationship she had with Dr. Parkinson was not right,” says Williams. “He seemed a little overinvolved. Her health under his care seemed to be deteriorating.”

Aldrich insisted that Parkinson was a brilliant doctor. He was kind and generous like no one else would be. They were lucky to have him there.

Geraldine Rasmussen was a bolder woman than most in her ward, and a lot of people in the county didn't like her. She was outspoken, maybe even a little brassy, and enjoyed tracking local gossip as much as tracing family history on her home computer. She didn't like what was happening to her sister, and she didn't trust Parkinson. She was even more upset when her mother, Dorothy Gray, began seeing him. But Gray, too, stood firmly behind the doctor. She had known him for 20 years as a church leader, and she believed in his goodness. For the sake of peace, they basically agreed to disagree within the family.

But as Williams learned more and more about the situation, he felt he had to act. “At that point, I started putting a lot of pressure on Gerry, telling her that you have got to go to the Medical Board,” he says. “You have got to start talking to other people.”

She did. And the town of Fairfield exploded.

In the spring of 1992, Geraldine Rasmussen officially complained about Parkinson to the Medical Board of California. In June, Rasmussen's aunt, who had been receiving chemotherapy treatments from Parkinson, died of

10/35cancer. Rasmussen's cousin, Carolyn Windham, went to see a lawyer about her mother's death. Windham, herself a Parkinson patient, was also uncomfortable with some of the doctor's practices. Parkinson had given Windham a lot of pelvic exams. In fact, she had had a pelvic exam nearly every time she saw Parkinson.

Before any official investigation into Rasmussen's complaint began, Geraldine Rasmussen called a meeting with the leaders of her church. It was held in July, in the offices of the Vacaville stake president, and Rasmussen's bishop. Louis Madsen Jr., a dentist and local Mormon leader — and Parkinson's good friend– as well as another counselor in the local stake were also there.

Rasmussen told the church leaders that she believed Parkinson had done bad things to her aunt, and continued to do bad things to her sister, her cousin, her mother, and other women who were his patients. Among other things, she told them that she thought Parkinson gave women pelvic exams — many, many pelvic exams — for no medical reason, overmedicated and misdiagnosed his patients, and used dangerous chemotherapy treatments. She also told them that she had filed a Medical Board complaint, and that her complaint was the subject of an investigation.

The men responded with complete disbelief. Rasmussen was accusing Parkinson of extraordinarily bad medical practices and sexual molestation. It was unthinkable that someone of Parkinson's stature would be guilty of either. Besides, they all knew him. They had known him for years. He was a leader in the church. He was one of them.

Madsen, in particular, was angry. He challenged Rasmussen to confront Parkinson with her allegations. Rasmussen refused. Instead, she sent a message through Madsen to Parkinson: “Free my people.”

No one ever uttered a bad word about MaryLynn Parkinson. People describe her as warm, friendly, vivacious, and fun, as outgoing as her husband was shy. She taught high school for years in Fairfield, and

11/35everyone seemed to know her. She was married to John Parkinson for 39 of her 60 years. She died of breast cancer on Sept. 16, 1992.

Upon her death, Parkinson began to behave strangely and make odd, conspiratorial allegations about people he considered to be his enemies. First, he arranged for security guards at MaryLynn's funeral. (He told Fairfield Police that he hired the guards because he'd been the subject of a campaign of stalking and harassment orchestrated by Rasmussen, her husband, and their friends.)

Later that month, Parkinson told police people had been following him from his office, around town, and to his home during the past four or five months because of a disagreement at church. Parkinson believed different people would pick up his trail through various parts of town, and all of this tailing, coordinated through electronic communications equipment, was led by Paul Rasmussen, who knew about such things.

Police surveillance turned up no such stalking conspiracy.

In December, Parkinson reported that the stalking had escalated, and as many as 100 people were following him around town. He also reported hearing footsteps on the roof of his office, which correlated with a break-in at Madsen's office across the breezeway. Police found shoe prints on the steel beams that cross an atrium/patio area in the medical building, and hand prints above a wooden bench. Two water and air hoses had been cut in Madsen's office, but nothing had been stolen.

In a letter memorializing the entire affair, Parkinson describes an incident that happened on the freeway on his way to work:

“While I was driving to work along a short section of freeway, my left front windshield was struck by a bullet fired from the rooftop of a building across the freeway. Fortunately, two months before, I had purchased a new car with extra thick, specially reinforced safety glass. The bullet left a small round hole in the first layer of my windshield, but thankfully did not penetrate the remainder of the glass. The windshield was examined by a ballistics expert who determined that the crater was not created by a rock,

12/35but by a bullet whose trajectory suggested that it was aimed at my chest. ... This incident ... gives a clear indication of the dangerous circumstances that surround me and of the viciousness of those who have created them.” [page]

The following April, with little fanfare and no initial public notice, Carolyn Windham, Geraldine Rasmussen's cousin, filed a lawsuit against Dr. Parkinson in Solano County Superior Court, alleging he had committed malpractice by performing unnecessary pelvic exams.

About a week later, Parkinson filed a lawsuit against Geraldine Rasmussen, Chance Williams, and a woman named Vicky Hardy, who didn't seem to have any connection to Parkinson or her fellow defendants. Parkinson alleged they had defamed him, based on what Rasmussen had said in her meeting with church leaders. The combination of these two lawsuits eventually made news in the Fairfield Daily Republic, kicking off a buzz throughout the community and the church.

Something else happened that same April, with little fanfare and little initial public notice: Dr. Parkinson married one of his patients — Anne Aldrich, the sister about whose medical treatment Geraldine Rasmussen had been so concerned. Aldrich and her son, Matthew, moved into the Parkinson family home. They still live there.

Everett Gremminger carries the largest caseload in the state Medical Board's Office of Investigation. He's not a man who's easily ruffled.

A 20-year veteran of the Oakland Police Department, Gremminger is a decorated narcotics detective who spent an entire career chasing big-time drug thugs. He wears the look of a retired cop: tall, portly frame, graying hair, glasses, comfortably worn face; a guy who's been there and done that. He might be intimidating, were it not for the folksy manner he projects almost immediately on meeting. Gremminger joined the Medical Board after retiring his shield in 1989. His new job is calmer, but the workload is no lighter, and a lot of the cases make even less sense than drug deals gone sour.

13/35Geraldine Rasmussen's complaint landed on Gremminger's desk because Gremmin-ger already knew John Parkinson, at least on paper.

Parkinson was on probation with the Medical Board of California for a 1990 incident. The state found that Parkinson had overtreated a patient who'd been injured in a car accident. (Parkinson maintains that he agreed to probation simply to settle the matter, because his first wife was ill and he was preoccupied with her care.)

And about the time Rasmussen made her complaint about Parkinson, auditors for Medi-Cal, the state agency that dispenses funds for medical treatment of the indigent, began questioning unusually lengthy chemotherapy treatments that other Parkinson patients were receiving.

Everett Gremminger smelled a problem. He had no idea how big it would grow, or how strange it would get. After the Fairfield Daily Republic ran its story about Carolyn Windham's lawsuit, and then more stories on the Medical Board's investigation, fear and loathing spread through the community like wildfire.

Initially, the Medical Board was looking to determine whether Parkinson had been negligent in treating cancer patients. But when prosecutors started reviewing medical records, they found that something was very, very wrong. The case changed before their eyes.

Gremminger talked to his wife. And then he talked to other doctors. He knew a lot about a lot of things, but pelvic exams weren't among them. The investigator set about the task of interviewing Parkinson's female patients. Because of the delicacy of the subject matter, he wanted their husbands to be present for the interviews. And many of those husbands had never heard about what went on when their wives went to see Dr. Parkinson.

Slowly, in interview after interview, an ugly pattern formed. Parkinson, it seemed, had women in the stirrups every time they walked in the door.

14/35Gremminger's phone rang constantly with calls from Parkinson patients. Some women had heard from their neighbors. Others had read newspaper stories — in horror. They'd had the treatments too. They didn't go to other doctors. They trusted Parkinson. They didn't realize anything was wrong.

Now they were scared. And embarrassed. And angry. About two dozen women signed declarations alleging inappropriate care. Another 30 or so called but didn't file official complaints.

The state Attorney General's Office prosecutes on behalf of the Medical Board. By June 1993, Deputy Attorney General Susan Meadows was convinced that the state needed to stop Parkinson from practicing while the situation was sorted out in court. She filed for a temporary restraining order. Every judge on the bench in Solano County Superior Court disqualified himself or herself from hearing the matter. The judges either knew the victims (one of whom worked in the court), or they knew Parkinson, or both. The matter of Dr. John Parkinson moved into Contra Costa County.

The quaint little town of Martinez is snuggled comfortably into gorgeous, pastoral, rolling green hills. During rush hour, the path through these hills contains some of the worst commuter traffic in the Bay Area, but Martinez itself still has a sort of rustic, throwback look. It is one of those towns where it is difficult to decipher what has been gentrified and what is just plain old.

There are two major enterprises that define Martinez in a commercial sense: the industrial tentacles of Shell Oil Co. and the civil business of Contra Costa County.

The county courthouse is a tall, pillared neoclassical building that sits atop a platform of cement stairs. Everything about it says that this is the home of justice, or at least a place where important things are done. [page]

And on July 28, 1993, it was packed with more than 100 people from Fairfield who showed up for a hearing on an order that would temporarily stop Parkinson from practicing at least some forms of medicine. Those in

15/35attendance were old, young, male, and female. Most were members of the Mormon Church. Many wore green ribbons, an unexplained but quickly adopted symbol of support for Parkinson. The crowd spilled from the courtroom into the hallway. There were whispers and stares. Neighbors educated each other on the players, and what they supposedly had done.

After the Attorney General's Office produced records on several Parkinson patients, the state's medical experts testified that Parkinson's course of treatment for those patients was negligent and improper. The Parkinson legal team, which included his son and another lawyer, argued that their client was a highly respected member of the community. The whole affair, they asserted, amounted to an unwarranted attack by a handful of misguided and angry women.

Judge Douglas Swager made what seemed like an odd compromise: Parkinson could not see female patients, pending the state's disciplinary hearing on his medical practice issues. But the doctor was free to treat male patients as he saw fit.

The news hit Fairfield doorsteps the next morning. Almost immediately, it became clear that the Parkinson matter was going to split Fairfield deeply.

In support of the doctor were many church leaders and a group called “The Committee to Support and Defend Dr. Parkinson.” The committee was headed by a man who'd been a lifelong friend of Chance Williams, Rasmussen's brother.

The committee placed fliers on parked cars, mainly near Mormon functions, that attacked women who had filed complaints against Parkinson. The fliers, titled “The Truth About Dr. Parkinson,” contained minitestimonials from patients and friends. One such testimonial came from a woman named Susan Collins, who stated: “My husband and I know personally the vengeful woman who is behind all of this tragic turmoil, and would like to go on record as testifying that she made the remark that she would get Dr. Parkinson if it was the last thing she did.”

16/35But the support of church leaders angered many people who knew the women complaining about Parkinson, and who felt they were being treated unfairly.

And the polarization seemed to affect everyone and everything. Some people stayed away from church activities. Friends argued. Neighbors stopped speaking. There was no middle ground in Fairfield. Parkinson was either a perverted quack, or a great healer and persecuted man of God. The choosing up of sides was accompanied by some strange sideline activity.

In October 1993, most of the women who'd made official accusations against Parkinson, many of whom were Mormons, received a letter from someone named Clyde L. Moore. The letterhead on which the missive came listed its origins as an entity called “Executive Services,” with post office box and phone numbers in Salt Lake City (home, of course, to the headquarters of the Mormon Church).

The letter stated that “a thorough investigation” had established Parkinson's innocence, and that the U.S. Department of Justice was investigating the California Medical Board. Neither claim was true. The letter also implied that the church was preparing to take legal action of some kind against Parkinson's detractors:

“While we are not involved in any official capacity with this investigation, we have been retained by authorities in Salt Lake City to contact Church members who may have information regarding these solicitations and request that they make complete and truthful disclosure of their knowledge to any General Authorities who may contact them and also to their local Church leaders. Some persons may wish to secure private legal counsel regarding any personal liability they may have for statements made or actions taken in response to the alleged illegal solicitations noted above.”

The Attorney General's Office investigated the matter as possible evidence of witness tampering and found that the post office box was registered to Parkinson's half-brother, Quentin Call. Parkinson had been in

17/35Salt Lake City for a church conference at the time the letter was sent, but denied any knowledge of the letter or its origin.

On another front, one of the state's witnesses, Cindy Weber, who was a Mormon, filed a sworn declaration redacting a previous declaration that accused Parkinson of misconduct. She said that Gremminger and a lawyer in the Attorney General's Office had coerced her previous, untruthful statement. The AG's Office denied her claims.

And Geraldine Rasmussen, whose complaint had kick-started the state investigation, received an anonymous photocopy of certain Mormon religious tenets, mailed from Provo, Utah. The photocopy said, in part:

“Cursed are all those that shall lift up the heel against mine anointed, saith the Lord, and cry they have sinned when they have not sinned before me, saith the Lord, but have done that which was meet in mine eyes, and which I commanded them.”

A crowd gathered at the old state courthouse on McAllister Street in San Francisco on the morning of March 2, 1994. It was the first day of what would become the second-longest adminis-trative hearing in the history of the Medical Board: The Matter of Accusation and Petition to Revoke Probation Against John Parkinson, M.D.

There is no jury in an administrative hearing. Each side presents its case to a judge, who makes a decision. The members of the Medical Board of California (12 doctors and five members of the public) then may either adopt that decision, or decline it. The board has the final word.

Parkinson was flanked by his lawyers, San Francisco attorneys Wayne Skigen and Richard Levine. One of Parkinson's sons, Dan, a contractor, drove him into the city every morning, and back home again in the evening after they'd huddled with the lawyers to discuss the day's events.

Deputy AG Susan Meadows was at the prosecution table, along with another lawyer from the Attorney General's Office. Gremminger was present nearby. Behind them were about 50 people from Fairfield, all

18/35wearing green ribbons, by now the universal symbol of support for Parkinson. [page]

Meadows began her case. The allegations covered behavior that ranged from the strange to the torturous. As the days went on, women revealed the most intimate details of their health problems, their personal lives, and what happened between doctor and patient in the private world of the examination room.

Taking the stand was particularly difficult for Marilyn Clark, a devout Mormon who runs a horse-breeding business with her husband, who holds a position in the church. Clark was keenly aware that the church leaders supported Parkinson.

On the stand, Clark told the judge how she first came to see Parkinson in 1981. Twenty-five years old at the time, she'd had four children in five years. She was feeling tired and depressed, and a woman from her church suggested that she go see Dr. Parkinson.

The doctor performed a typical pelvic exam: Clark lay on her back on the exam table, with her buttocks at the end of the table, knees in the air, and feet in stirrups on either side of the end of the table. Typically, doctors use something called a speculum — a metal or plastic device inserted into a woman's vagina to view her cervix and take tissue samples. Clark testified that Parkinson never used a speculum.

The doctor told Clark she had a uterine infection, for which he prescribed antibiotics, and anemia, for which he prescribed iron tablets. Later, he would inject iron directly into her muscles, and then into her veins. Parkinson prescribed estrogen replacement for Clark in levels appropriate for a woman entering menopause, not someone in her mid-20s.

Clark testified that she saw Parkinson twice a week for the next year. Each time, the doctor performed a pelvic examination and reported that she had a vaginal infection of some kind, though she never had any symptoms of such a problem. Even though these supposed infections continued for a year, Parkinson never referred Clark to a specialist in gynecology.

19/35“He had me convinced that I had those infections, and that I needed to be there to get the treatment, to get the antibiotics, and to take care of that, and the anemia,” she told the court.

Finally, Clark's arms were so sore from the iron shots that she couldn't take it anymore. She quit going to Parkinson and has never been diagnosed with the same problems by any other doctor.

The other women's stories were similar. They told how Parkinson treated them for vaginal infections and inflammation, endometiritis, and infections of the uterus, even though many of them never had symptoms suggestive of such disorders.

Parkinson had performed pelvic exams several times a week — sometimes as often as every day, and in one case for a duration of 14 years. He was frequently alone with the women — even though general medical rules require a nurse to be present during any gynecological examination — and often did not wear gloves, even though use of gloves is standard for a pelvic exam. (Parkinson told the court that he is allergic to latex, and was unable to adequately perform examinations with other types of gloves.)

Nonetheless, the women continued to come to his office for treatment. He told them that they were sick, and he could make them well. And they believed him. He was a well-respected doctor. He held important positions in the local hospital. He did not charge those who had no insurance or limited means. And for many of the women who walked into his examination room, John Parkinson was not just a doctor. He was also their spiritual leader.

Kathleen Grose came to see Parkinson when she was 37 years old and had already been diagnosed with breast cancer. Two years later, she underwent a partial mastectomy. Although Parkinson held himself out to be something of a cancer specialist — his letterhead reads “Internal medicine-hematology-oncology” — he certified only in general medicine.

20/35Even so, Parkinson began giving Grose chemotherapy treatments — that is, a cocktail of toxic chemicals generally used in short intervals to attack cancer. He continued to administer what he termed “maintenance chemotherapy” for 14 years. The state could not establish what kind of damage 14 years of toxic chemicals might have done to Kathleen Grose because prosecutors could not find that it had ever been done before. There are no clinical trials for such a thing.

Parkinson, it seemed, was experimenting on his patients.

Grose told the judge that she had received pelvic examinations, during which Parkinson manually applied a salve to her vaginal area as frequently as three times a week for five years. Her medical records revealed that, during one particular six-month time period, Grose had received more than 200 pelvic exams. When she asked for medicine she could apply herself, Parkinson said no; he needed to examine her.

Parkinson provided complex scientific and medical explanations for his treatments. He said that he was best able to monitor estrogen levels and infection through pelvic examination. And, he suggested, he was able to insert a speculum so gently that a patient may not have realized he was putting a 6-inch piece of plastic into her vagina.

And the chemotherapy? Parkinson and his expert witnesses testified that his chemotherapy regimes were successful, because his cancer patients remained alive for longer than five years.

Judge Jonathan Lew agreed to accept only a fraction of the 129 witnesses Parkinson's attorneys submitted to testify on behalf of the doctor's personal character and the quality of his care. Again, Susan Collins was one of them.

“I know his character,” she told the court. “I've been around him and worked closely enough with him, I've seen how much he cares about people, how compassionate he is. He never makes any kind of an

21/35advance toward a woman. He's very, very proper. And having been my daughter's physician, I know that she considers him to be just above and beyond reproach.” [page]

Geraldine Rasmussen's own mother testified against her, saying that Parkinson was a terrific doctor and that Geraldine had vowed to get even with Parkinson.

Louis Madsen Jr., the dentist, stake president, and friend of Parkinson, was emphatic in his support of the doctor:

“I would not dare go before my God and not defend this man. That's how strongly I believe in him. ... This man is extraordinary in every way that I have observed.”

The hearing was finally over, nine weeks after it started. But Lew didn't issue his order in the case until March 1995, a year after the hearing had begun.

But when he did rule, Lew stunned Parkinson, finding him guilty of practicing outside the accepted medical standard and of gross negligence. The judge did not find Parkinson guilty of sexual abuse or misconduct because, he said, the state had not proven that Parkinson received any sexual gratification from his acts.

The Medical Board revoked Parkinson's license to practice medicine in the state of California, the harshest penalty available. The following day, Everett Gremminger and an agent of the federal Drug Enforcement Agency showed up at Parkinson's office to repossess his license, physician's card, and any illegal drugs he had on hand.

Solano County District Attorney David Paulson declined to prosecute John Parkinson because, he said, there was no evidence to prove Parkinson had an intent to sexually abuse the women, or that he had been sexually aroused by his “examinations.”

22/35Kymberly Collins grew up near Vacaville. Her parents had always kept their family involved in church activities. In fact, her mother, Susan, had at one point been involved in leading a youth organization in their stake.

For the most part, Kym's life followed a common plan: She graduated from Vacaville High School and went to Brigham Young University. She took a year off to do missionary work in Spain, and came back to finish college with a major in political science.

On one particular afternoon at BYU, Kymberly ran into Christina Parkinson, one of John Parkinson's children, who was visiting the area with two of her sisters. The young women were close in age and both grew up around Fairfield. They knew each other through the church and had mutual friends, but they were not particularly close. Yet for some reason, on that particular day, they seemed to bond. Christina, who goes by the nickname “Teeny,” had served on a mission in Portugal at the same time Kym was on a mission in Spain. Teeny had just lost her mother to cancer. Kym had recently lost two brothers. They had a lot to talk about. In fact, they would spend nearly all evening chatting in Kym's apartment.

Teeny Parkinson talked about the problems her father was having with the state Medical Board, which were by then common knowledge and the subject of much gossip in the Fairfield community. She thought the allegations were ludicrous, the result of a bitter woman's vendetta against her father, whom she loved dearly. The charges sounded ludicrous to Kym as well, and she easily adopted Teeny's viewpoint. In fact, she was ready to help. There is some disagreement about whether Kym Collins told Teeny Parkinson to talk to her mother, or whether Teeny Parkinson asked for her mother's help. In any event, after Teeny returned to Fairfield, she and her sisters somehow connected with Susan Collins.

Before long, Collins was heavily into the cause of supporting Dr. John Parkinson. She began writing letters and otherwise doing all she could to help protect the reputation of Parkinson.

23/35When Kym finished school at BYU, she came home to Fairfield without much of a plan for the future. She was 26 years old and very pretty, with blond hair that trailed down past her shoulders. But her friends were getting married, and she wasn't. She went to stay with relatives in Florida for a while and considered getting a job there, but ultimately decided to return to Fairfield.

Teeny was teaching school by then, and she and Kym had become close friends. Their families had also become close, celebrating Thanksgiving and Christmas together. Both Kym and Susan helped with the planning and execution of Teeny's wedding. Kym and Teeny passed out fliers in support of John Parkinson.

Kym had periodically suffered from irregular menstrual periods and pain as far back as when she was in Spain. One day, when they were in Parkinson's office, Teeny mentioned Kym's problem to her father. Kym said her periods were still irregular. Parkinson suggested he give her a shot that would help. She agreed, without even asking what was in the syringe. And then Parkinson asked her to come back the next day, so that he could examine her. Kym told Parkinson that she didn't have insurance, and couldn't pay him. Parkinson told Kym that treating her would be a way he could repay all that her family had done for him.

The following day, Parkinson performed a perfectly routine examination — including a pelvic exam and Pap smear — on Kym Collins. He gave her a robe to wear, and one of the ladies who worked in his office was in the exam room the majority of the time they were there. Parkinson told Kym that she had a low-grade infection, and that he wanted her to return within a couple of days. He also gave her two estrogen shots.

From that point on, Kym visited Parkinson's office regularly.

Procedures changed a bit after Judge Swager issued the restraining order prohibiting Parkinson from seeing female patients, but the doctor didn't stop treating Kym. Instead of going into the usual exam room, Parkinson ushered Kym into another room, which was cluttered with plants, boxes, and medicines. [page]

24/35In the center of the room was an examination table. The window had been blocked out with insulation. Parkinson followed Kym into the room and locked the door, telling her that he was concerned about people following him around and nosing into his business. There was no robe and no assistant. Kym was a little uncomfortable undressing in front of Parkinson, but didn't think much of it. He was her church leader, and a doctor, for heaven's sake.

She removed her pants and her underwear, climbed up on the table, and put her feet in the stirrups. Parkinson examined Kym and said it looked like she had a yeast infection. She remembers that Parkinson mixed an over-the-counter medication for yeast infections with vaseline and rubbed it around the outer part of her vagina, and then inside. Next he stuck two fingers into her vagina, pressed on her abdomen, and asked if she felt any tenderness.

He gave her a breast exam. And he applied more of the Gyne-Lotrimin mixture inside and out. He was massaging, he told her, to make sure the medicine was absorbed. And then he reached down, took a syringe, and gave Kym a shot in the lower left side of her buttocks. She says he put his hand inside her, pressing against where the shot was, and told her this would prevent bruising. This activity, she says, lasted about 20 minutes. The doctor gave her two or three more shots, repeating the process each time.

Parkinson talked about the injustice of the Medical Board situation, and about the women who had wrongly accused him. The entire visit lasted about an hour. And when it was over, Kym says Parkinson told her that her receptors were down, and her body wasn't receiving the estrogen it needed. She would have to come back for regular treatment.

Before long, Kym Collins was seeing Dr. Parkinson three to four times a week.

25/35“He said that I had a problem producing estrogen, and that it would be hard for me to carry a baby,” Kym says. “So I asked him if I'd be able to have children, and he said under his care I'd be able to.”

The visits gradually grew to nearly two hours in length and sometimes also included gamma globulin shots and B-12 shots. In January 1994, Kym went back to Salt Lake City. She began bleeding so severely that she had to see a doctor there, who gave her a shot to stop her menstrual period. When she came back, Kym did not go to see Parkinson; she did not want to get back into the constant, time-consuming office visit routine. But, she says, Parkinson called her. His daughter had mentioned that she was back in town. He was worried about her, he said. She needed to come by the office. So she did. Parkinson continued to treat Kym while his license hung in the balance during the Medical Board hearing in San Francisco. At the end of that year, Kym moved to S.F. for three months. Parkinson treated her on the weekends.

“It wasn't that I was feeling sick. It was the fact that I knew when I saw him, and he said that I looked low and I looked down and I didn't look healthy, I knew I needed to start seeing him again, because I didn't want to jeopardize the fact that I could have children.”

One day, when Kym Collins and her mother were shopping at Solano Mall across the street from Parkinson's office, Susan suggested they buy a box of See's candy and take it to Parkinson. Susan had been told that Parkinson was feeling down about all of the problems surrounding the challenge to his medical license; the doctor could probably use some cheering up. At the office, Parkinson inquired about Kym, and suggested her mother might need estrogen therapy because she was going through menopause. Grateful for the support that Susan had provided him, Parkinson said he was happy to treat her at no charge.

Susan's visits were much the same as those of her daughter, with Parkinson giving the estrogen shots and massage routine behind the locked exam door, underneath the blocked-out window, wearing no

26/35gloves. These exams, too, lasted up to two hours. Sometimes Susan's husband would drive her to the appointment and wait in the waiting room.

Parkinson also began a particularly odd treatment for Susan's lower back pain. The exact details of this treatment have never been fully explained, but it generally went like this:

Parkinson instructed her to remove her underwear and stand facing the exam table with her legs spread apart, one foot up on a stool, and her dress pulled up over her back. While she leaned over the exam table, Parkinson would insert his hand high up into her vaginal canal, and attempt to reach her lower back muscles.

“He said that he needed to get to the muscles that were in the center of the lower back; that the muscles and tendons all came to this area, and that he could pull on those and loosen them because that seemed to be where a lot of my back pain was,” Susan says.

During treatment, they would converse about spiritual matters, or about Parkinson's case with the Medical Board, which he was appealing. Sometimes, during treatment, Parkinson shared his weekly Sunday school lesson. The back treatment was very painful, and after about 10 visits, Susan says she told Parkinson she couldn't endure it anymore.

By this time, Parkinson's medical license had been revoked. In fact, he signed regu-lar declarations saying he was not treat-ing patients.

Yet Parkinson continued to see Kym, Susan, and a few other women illegally. They continued to come to him because they believed, as he told them, the entire affair had been an awful miscarriage of justice that would surely be straightened out in time. The women would park in back of his office and tap on the window; he would let them in through the back door, which he kept locked. [page]

At some point, Susan Collins mentioned to Parkinson that she was worried about Kym, who seemed kind of down about not having a husband, a boyfriend, or a plan for the future. Susan asked Parkinson to encourage

27/35her daughter, and give Kym's esteem a boost.

A few months after the Medical Board decided to revoke his medical license, Parkinson wrote a poem that he gave to Kym at the end of one of her visits. Parkinson told Kym that he was moved by something outside of himself to write this:

With anticipatory gaze,

We looked upon forthcoming earthly haze. Eternity loomed.

Celestial knowing of all that God bestowed; Tiny stream of microcosm time, to

be immersed.

Promises hidden by forgetful veil,

Yet to be fulfilled in Earthly pale.

Thereby joyous reunion,

Then eternally forged

Members of the Mormon faith believe they experienced an existence before their life on Earth. They also believe that Earthly life is a temporary state, and that they go on to live with God in heaven. Couples married in the Mormon temple are believed to be sealed together for eternity (this life and the next). Kym thought the poem related to her future mate. Parkinson told her that she would find out the full significance of the poem in time.

After an examination a few weeks later, Parkinson presented Kym with a picture of a treasure chest, attached to balloons that floated through the air. He asked her to close her eyes and open her mouth. And then he carefully placed a piece of Lindt chocolate on her tongue. Two days later, after another exam, Parkinson gave Kym a small prescription envelope. Inside was a two-dimensional treasure chest, matching the one in the earlier picture. Inside the smaller chest was this poem:

By now you may know the “we” is us;

And a treasure you are

28/35to one most timorous

Kym stuck the poem in her pocket and left. It made her feel uncomfortable. At first she thought Dr. Parkinson had fallen in love with her. And then she thought that was crazy. She must've blown the whole thing out of proportion. Kym kept her appointment with Parkinson the following Monday. He continued the usual shot and massage routine. And while she lay on the table, feet in stirrups, he brought up the subject of the poem. She described it this way:

“We first started out talking about the significance of the poem and that the 'we' was referred to as he and I; and then he said that he had been attracted to me from the first time that I'd known him from when I was back in college. And he had said that he couldn't deny it at that time, he had a physical attraction to me.”

Kym was stunned. Most of all, she wanted to get off that table. Parkinson, she says, asked her how she felt about him, and she told him she did not share his feelings. He said he was glad it was out in the open. Finally, the exam was over. They walked to the front and waited for her mother to pick her up. Parkinson told her again that he was glad it was out in the open. It was unbelievable to Kym.

When Susan arrived, Kym seemed anxious to leave, but her mother didn't think much about it. They left the doctor's office and drove across the street to shop at the JCPenney at the mall. But Kym began to get short with her mother. Susan had to stop at Raley's grocery store; Kym just wanted to go home. Susan studied the salad dressing selection. She turned to her daughter and asked her what kind of dressing she should buy.

Kym burst into tears. She mumbled something about getting out of there. Completely at a loss, Susan handed her keys to her daughter, who turned and left the store. Susan paid for the groceries and headed through the parking lot, anxious to find out what was going on.

29/35They talked in the car. And Kym told her mother what had happened at Dr. Parkinson's office. The meaning of the incident would not fully sink into Susan Collins' brain for some time. But then, it was as if everything had been turned upside down, everything she believed was suddenly wrong. Their safe, comfortable, suburban world was shattered in such a way that they might never get over it.

In the car on the way home, and for a very long time after that, Susan and Kym Collins would wonder how things could have gone so far awry, and how they could ever have been a part of it.

Everett Gremminger thought he'd never stop hearing about John Parkinson. After the Medical Board hearing that should have ended Parkinson's career, Gremminger received anonymous phone calls from people saying that Parkinson was still treating women. But there wasn't much he could do about it without any evidence. And then, in August 1995, he received the call alleging Parkinson had molested Susan and Kym Collins. Gremminger interviewed the Collins women, and then he called the Fairfield Police Department. This was no longer a matter for the Medical Board.

The following Friday morning, Parkinson left his office, got into his dark green Acura, and headed out of the parking lot. He had an appointment with U.S. Rep. Frank Riggs. Parkinson was prepared to explain to Riggs the details of a travesty that had been perpetrated against him by the Medical Board. But Parkinson never got out of the parking lot.

An unmarked police car blocked his exit. More patrol cars surrounded him. A cop leaned him against his car and patted him down. Fairfield Police Detective Joe Quinn began asking him questions about the Collins women, his medical license, and where he was going. Parkinson yelled to a janitor who'd come to see what was up: “Get Lou Madsen.” [page]

Madsen came out of his office in short order. Parkinson was very concerned about his appointment with Riggs, and told Quinn that he had some important papers he had to deliver there. They went into Parkinson's

30/35office and arranged for Madsen to fax the papers. (Riggs did not return calls seeking comment.) Then Parkinson was booked into Solano County Jail on charges of felony sexual assault and practicing medicine without a license.

It took a plethora of police officers the rest of that day and some of the next to remove and catalog what was confiscated from Parkinson's office. There were boxes upon boxes of drugs — outdated medicines and the controlled substances that Parkinson had told a DEA agent months before he didn't have. There were gallons of K-Y jelly, creams, ointments, and piles of other unknown substances. Police found needles and syringes everywhere, even underneath potted plants.

Parkinson's office was known to be a mess — patients often joked about not being able to walk through the clutter. But this was worse than a mess. There were boxes of papers everywhere, magazines and journals scattered about, dead and live plants, fertilizer, bags of candy and food on the counters.

More than 10 rubber-glove-wearing police officers searched Parkinson's seven-bedroom home in the quiet, upscale neighborhood of Willotta Oaks, just outside of Fairfield proper. The place was an unbelievable wreck. Parkinson's wife Anne, still clad in her nightgown, was in the bedroom when the cops arrived at 11:30 a.m. The search did not stop until 9:30 that evening. Police found more drugs, syringes, needles, and ointments in cabinets and on counters throughout the master bedroom and bathroom, in the basement, in other parts of the house, even in the refrigerator. One officer on the scene said they didn't realize there was a tub in one of the bathrooms until they moved some of the stuff dumped in it. In total, police removed eight truckloads of drugs, syringes, medicines, vitamins, and the like from Parkinson's home and office.

While John Parkinson was preparing to defend himself against criminal charges in Solano Superior Court, yet another drama was unfolding in Fairfield. It had nothing whatsoever to do with pelvic exams.

31/35Parkinson's 25-year-old son James had long suffered from schizophrenia and lived in a Fairfield mental health facility called Stargate. That is, until the afternoon of June 8, 1996, when he ran away. What happened next remains the subject of intense controversy and a civil lawsuit against Fairfield Police.

What's clear is that James had slipped into a full-blown psychotic episode. Shortly after 3 p.m., he kicked off his shoes, told no one in particular that God had instructed him to do three somersaults, and took off across Kidder Avenue doing just that.

Within minutes, Fairfield Police began receiving calls from nearby residents about a naked man — James stripped shortly after leaving the Stargate facility — who was running through the neighborhood, breaking windows. By now, James was bleeding from cuts on his hands and arms, but that didn't slow him down any. When the police finally arrived, a growing knot of neighbors pointed them toward the Birchwood apartment complex.

According to police reports, Fairfield Officer Bob Bunting chased James around the pool at the complex, but James wasn't losing any steam, nor was he interested in anything Bunting ordered him to do. Police officers continued to arrive (there would be nine by the time all was said and done), and paramedics were standing by until the area was “secured.”

James didn't have a weapon of any sort. He didn't even have shoes or clothes.

On three occasions, James ran toward Bunting, and on all three occasions, Bunting sprayed James with pepper spray. It didn't stop him. While they continued to run around the pool, another officer shot James with a Tasertron, the electric stun gun used by the Fairfield Police Department. Two darts landed in James' upper back and butt, and attached wires sent an electrical current into James' body. He hit the ground, rolled over — which pulled the darts out — and started to masturbate.

32/35But the episode wasn't over. In short order, James jumped up, announced, “You can't keep a good man down,” and took off running again. The officer tried to fire the taser gun again, but it malfunctioned. Finally, one of the cops hit James with a shoulder block and knocked him to the ground. Three more cops held him down while another handcuffed him.

Then James began to suffer a seizure. The cops rolled him on his side and, they reported, the seizure stopped. A few minutes later, paramedics showed up. They strapped James onto a gurney, on his back. Somehow, James ended up on his stomach and seemed to calm down. Paramedics were preparing to treat him when they realized he wasn't breathing anymore. His heart had also stopped. James Parkinson was pronounced dead at 5:11 p.m., shortly after his arrival at NorthBay Medical Center. The event was officially termed “sudden death following a violent struggle.”

It is probably impossible for anyone else to know or feel the impact that such a troubled life, and tragic death, has on a father.

By the time John Parkinson finally came to trial on criminal charges in May 1997, he (and his insurance company) had already settled 16 malpractice suits. San Francisco Superior Court Judge William Cahill had upheld the Medical Board's decision to revoke Parkinson's medical license. The doctor had spent 33 days in jail, during which time he was isolated from the general population. But he'd eventually made bail, and since then, he'd been at home with his family. The court also allowed him to go to church. Much of his time was devoted to preparing for the trial. [page]

Parkinson's attorneys argued unsuccessfully for a change of venue. The court went through a series of judges trying to find someone to hear the case who did not have a conflict of interest of one sort or another, and finally landed with Solano Superior Court Judge James Moelk. Likewise, jury selection seemed to take forever. The court went through 120 prospective jurors before seating the seven women and five men who would decide the doctor's fate.

33/35The Parkinson case was huge news in Solano County. The Fairfield Daily Republic had covered every step leading up to court. The city was now completely divided into guilty and not-guilty camps. People would stop Deputy District Attorney John Kealy in the hallway, in restaurants, even at his daughter's music recital to talk about the case. The courtroom was packed every day, mostly with Parkinson supporters. As time wore on, they seemed to be losing ranks but were still a viable force.

John Parkinson represented everything that this community believed in. To believe that he was guilty of the accusations against him meant believing that something vile and disgusting lay behind a man who walked among them, and who led them. If that dark side was somehow inside Dr. Parkinson, it could be inside anyone. And for many people of Fairfield, that prospect was just unthinkable.

The Collins women told their stories matter-of-factly on the stand. Parkinson was smart and articulate with his testimony. He said that he treated the women after he lost his license because they begged him to. He denied ever making a pass at Kym, and said that he'd given the poem to her because Susan had asked him to cheer her daughter up. Kym misunderstood its meaning, he said. Parkinson told the court he locked the exam room door to keep the janitor from coming in accidentally, and he'd blocked out the windows because construction workers were frequently on the roof of the building next door.

On June 2, after a day-and-a-half of deliberation, the jury convicted John Parkinson of 16 felony counts of sexual penetration and two felony counts of practicing medicine without a license. He was acquitted of illegal drug possession charges. Moelk sentenced Parkinson to six years in prison, but delayed the sentence pending an appeal.

Before that sentence was handed down, more than 125 people wrote letters to the court praising Parkinson as an exceptional, kind, generous, caring, and morally sound man.

34/35Kym Collins moved to Southern California.

Rasmussen and her husband moved to a small town in Arkansas.

In his sentencing, Moelk noted that Parkinson had groomed his victims — he established relationships whereby the women felt obligated because he was treating them for free, and intimidated because he insisted the treatment was medically necessary. Moelk also noted that Parkinson had used the Collins' religious faith and commitment, and their family friendship, to gain their complete trust.

“He has given the impression that he is indeed above the law, and seems convinced that the only one that can pass judgment on his behavior is not of this earth,” Moelk wrote.

In September of last year, Dr. John Parkinson, through his new lawyer, George Costirillos, filed an appeal of his criminal conviction. In the appeal, he alleges that one of the jurors, a nurse, used her medical knowledge during deliberations in the case. He alleges that by doing so, she acted as an unsworn witness. The appeal is pending.

Meanwhile, John Parkinson remains at home, where he gardens, reads, and trains his pet cockatiel. One of his sons, his wife Anne, and her son live with him. The one thing that Geraldine Rasmussen and Chance Williams set out to accomplish nearly six years ago — to keep Parkinson away from a member of their family — is about the only thing that has not happened in and around the usually quiet town of Fairfield, California.

35/35 -

4. Doctor Ordered To Prison in Molest Case / Charges brought by 2 female patients

FAIRFIELD -- Capping a scandal that bitterly divided Solano County's Mormon community, a Fairfield doctor and former high church official was jailed yesterday for his 1997 conviction on charges that he molested two female patients.

Dr. John Parkinson, 68, was taken into custody after a Solano County judge ruled that a juror who allegedly harbored a grudge against the doctor had not committed misconduct or acted unfairly in his case.

Judge James Moelk's ruling came as a relief to prosecutors who have waited three years to see a six-year prison term imposed. Parkinson had remained free on house arrest pending appeals.

"I'm glad it's done," said Solano County Deputy District Attorney John Kealy. "It is very frustrating not to see justice be finalized."

Parkinson's two victims, a mother and her daughter, were not present for the sentencing. They were members of Parkinson's church, where he held the position of Mormon stake president, and were longtime patients who claimed he conducted pelvic exams on them for his own sexual gratification. Parkinson's medical license was stripped by the state in 1995.

Parkinson, who was a general practitioner, has always maintained his innocence, saying he is the victim of a setup by opponents in the church. As he had throughout his trial and in other court hearings, Parkinson reacted stoically yesterday to Moelk's ruling. He handed his watch and other jewelry to his wife during a court break and was led by bailiffs into custody.

Parkinson's lawyers have argued that a woman who served on the jury held a longtime grudge against him after working briefly with him in the 1980s as a nurse. The same juror was accused of improperly giving her medical opinion while the jury was deliberating on the charges.

Parkinson was ultimately convicted of 16 sex crimes and two counts of practicing without a medical license.

His attorney, George Cotsirilos, tried unsuccessfully yesterday to keep his client out of jail pending appeal. He told Moelk, "Justice may not be as quick as some might like, but if it's done too fast, it's not justice."

But the judge disagreed and declared, "I am not going to grant any further bail." Parkinson will remain in the Solano County Jail in Fairfield until at least May 1, when a hearing will be held to determine whether should receive any credit for any jail time he served before he was convicted.

Outside the courtroom, Cotsirilos called Moelk's ruling "incomprehensible" and said, "It is one of the worst rulings I've seen in 22 years."

Parkinson's son, Dan Parkinson, called Moelk "the most dishonest judge I've ever seen.

"It just shows the politics of the case," he added, as family and friends consoled each other.

-

5. Solano County court records search 1

Documents

Have docs or info? Add information

Criminal case documents

Floodlit does not have a copy of a related probable cause affidavit. Please check back soon or contact us to request that we look for one.Civil case documents

Floodlit does not have a copy of a related civil complaint. Please check back soon or contact us to request that we look for one.Other documents

Floodlit does not have a copy of any other related documents. Please check back soon or contact us to request that we look for some.Add information

If someone you know was harmed by the person listed on this page, or if you would like us to add or correct any information, please fill out the form below. We will keep you anonymous. You can also contact us directly.

Crime state:

Crime state:

Alleged crime scenes:

Alleged crime scenes: