The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (commonly known as the Mormon church) has long positioned itself as a leader in handling abuse, with officials claiming its approach is the “gold standard” and that “no religious organization has done more.”

But a startling discovery from a 2023 lawsuit challenges that narrative.

A System Shrouded in Secrecy

“Why didn’t they call us in? Why didn’t they call the kids in?” — Jane Doe

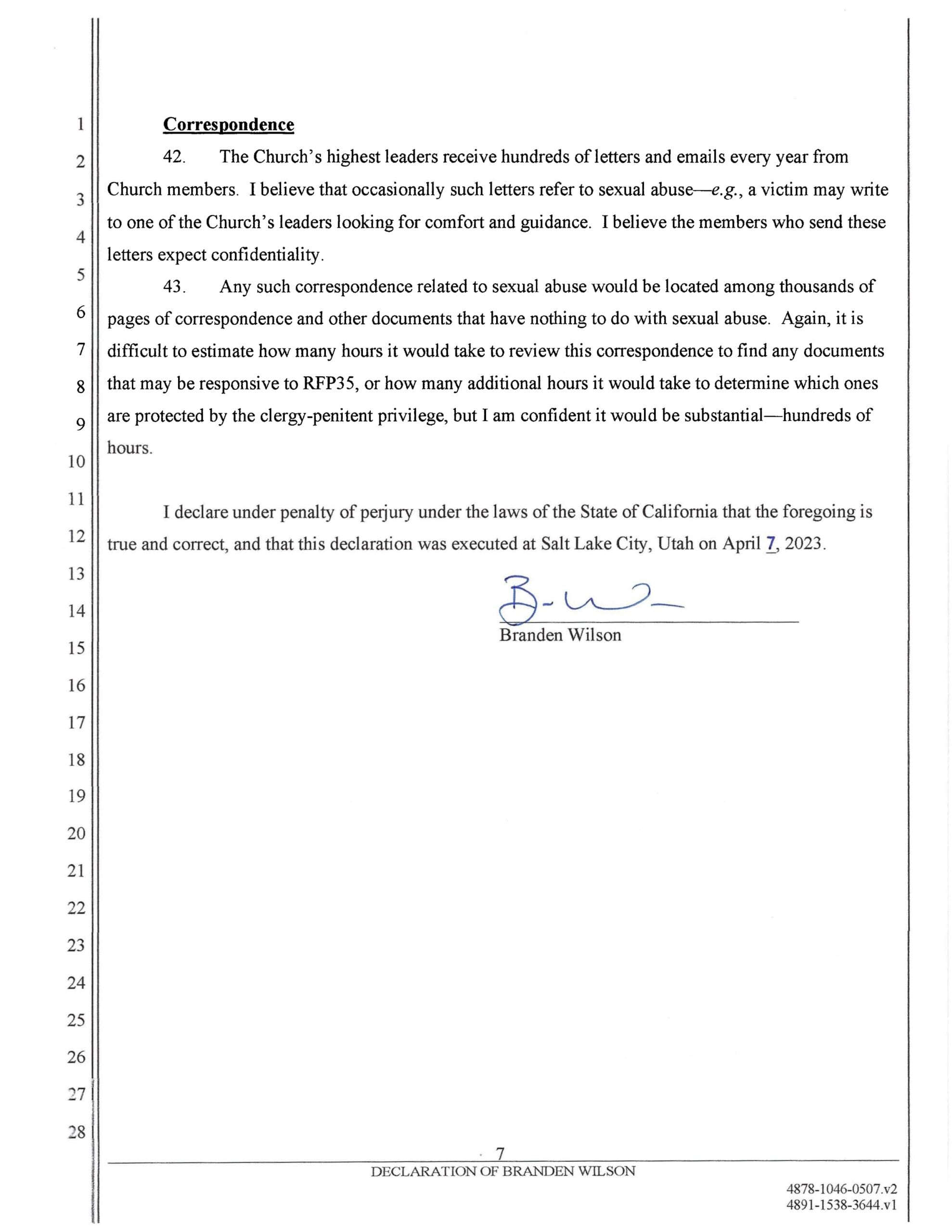

In a seven-page declaration filed in 2023 during a California civil lawsuit against the church, its risk management director Branden Wilson stated:

“The Church does not keep a repository of documents relating to allegations, claims, or notification of child sexual abuse. There is no ‘sexual abuse’ file.”

Wilson further explained that the church does not track members’ positions (callings) beyond bishop or stake president, and retrieving any related records would require manual sifting through unsorted disciplinary files – a process complicated by redactions and legal protections.

This admission came in response to plaintiffs seeking documents on abuse claims from 1990-2005; the church resisted production, citing sacred protections, before settling confidentially.

Wilson’s declaration paints a picture of an organization that prioritizes secrecy over systematic tracking, even as it faces hundreds of lawsuits alleging failures to report abuse.

- LDS church risk manager Branden Wilson declaration, April 7, 2023, page 1

- LDS church risk manager Branden Wilson declaration, April 7, 2023, page 2

- LDS church risk manager Branden Wilson declaration, April 7, 2023, page 3

- LDS church risk manager Branden Wilson declaration, April 7, 2023, page 4

- LDS church risk manager Branden Wilson declaration, April 7, 2023, page 5

- LDS church risk manager Branden Wilson declaration, April 7, 2023, page 6

- LDS church risk manager Branden Wilson declaration, April 7, 2023, page 7

Contrasting Claims: Randy Austin’s Defense and the Reality of Secrecy

“We are a family. A family keeps things private. A family draws close together. These things are to be kept private.”— Boyd Packer, Mormon apostle

Last week, at a FAIR conference in Lehi, Utah, attorney Randy Austin – a Kirton McConkie shareholder who has handled hundreds of abuse cases for the Mormon church – touted its clergy help line as a tool that ensures “a child’s safety always comes first” and that the church “never, ever, ever, ever leave[s] a child in harm’s way, ever.”

Austin argued clergy-penitent privilege, protected in 37 U.S. states, encourages more abusers to confess, leading to help before they perpetrate and fewer victims harmed.

Austin shared an example: A bishop, informed by a Boy Scout of abuse by his scoutmaster, called the help line and was advised to cancel a campout and report to police, resulting in the abuser’s conviction.

Online, Mormon apologist Jasmin Rappleye echoed this in a video, claiming privilege fosters reporting and reduces harm.

But critics question: How can the church evaluate its system’s effectiveness without records? Wilson’s “no file” claim contradicts prior statements, like predecessor Paul Rytting telling an Idaho victim he could check help line logs – logs another official said are destroyed daily.

The help line, reportedly receiving 20,000 calls in 2001 alone (with membership up 54% since), directs bishops not to report confessions without legal guidance – often prioritizing church protection over immediate action.

No more “trust me bro.” It’s time for hard facts.

In the Paul Adams case, a Bisbee, Arizona bishop’s silence after a confession allegedly allowed abuse of Adams’ daughters to continue for seven years.

In the case of David McConkie, abuse allegedly continued for up to nine more years after a Colorado bishop first learned of it, while McConkie became a bishop and stake president.

In Michael Jensen’s case, the alleged abuse of over 40 children went on for years, despite multiple bishops and a stake president being made aware and one calling the church’s help line. Documents uncovered by Floodlit show the church spent nearly $60 million to defend and settle a resulting lawsuit.

The McConkie Connection: A Legacy of Suppression

Randy Austin’s longtime employer, Kirton McConkie, was co-founded by Oscar McConkie Jr., brother of Mormon apostle Bruce McConkie. (Recently convicted David McConkie is a grandson of Bruce.)

In a 2017 oral history interview, Oscar McConkie, who died in 2020, shared the story of working on a case for the Mormon church and preventing a bishop from having to testify due to “clergy privileged” information.

“A bishop had [been] subpoenaed to come and testify. Comes to me as represent – I represent the church. I make a motion to quash the subpoena based on the fact that the only thing the bishop knows about it is clergy privileged, and that he can’t be testifying about it. And, so I take the bishop down to the court and they’re trying the case, and as I walked in the judge recognized me and saw that I had a man with me, and he announced from the bench: ‘For the record, I see Mr. McConkie and the bishop have arrived, we’ll take a 10-minute recess and you fine lawyers will meet with Mr. McConkie, and you’ll determine whether the bishop can testify, and if he can testify, what he can testify about. And then he says for the record, ‘Now for the record, if it’s gonna help you lawyers in making this determination, this court is gonna do just exactly whatever Mr. McConkie says.’ Now, you gotta practice law a long time to get that kind of, that kind of treatment.” – Oscar Walter McConkie, Jr. interview, Salt Lake City, June 26, 2017, recording 2, 1:17:35 to 1:19:01

Floodlit is trying to determine the identity of the accused; multiple cases exist that appear to line up with McConkie’s retelling.

A Pattern of Failures: Beyond Bisbee and Isolated Incidents

“I was sitting in a room, full of women, who had been sexually abused by a family member — most of them [saying], ‘My father abused me. I told the bishop. Nothing happened.’ I just knew that wasn’t going to be my story. I wasn’t going to allow that to be my story.” — Jane Doe

Floodlit’s database reveals the Bisbee, Arizona case is no anomaly. We’ve documented:

- 374 instances where Mormon leaders allegedly perpetrated sex crimes or failed to report abuse to authorities.

- $52 million paid in settlements after alleged failures.

- 80 reports of abuse in LDS buildings, including temples.

- 77 convicted former Mormon bishops.

- 94 ongoing criminal cases and 122 ongoing civil lawsuits involving Mormon abuse allegations.

Examples abound:

- Kenny Ray (1984, Arizona): Multiple bishops knew of abuse for up to 16 years but didn’t report; earliest known sex abuse lawsuit against the church.

- Steven Hammock (1989, Utah): Church refused to divulge confessional info; abuse survivor Jane Doe won $150,000 after years of litigation.

- Stephen Young (Idaho, 2010): Up to 15 officials failed to report confessions of infant abuse; Austin defended, saying handling was different in the 1980s.

- Michael Jensen (2013, West Virginia): Church spent nearly $60 million defending failures; Rytting emailed attorneys (including Austin): “He’s not the only one sick of this case.”

- Terry Allen (1987, California): Bishop’s failure to report allegedly enabled abuse of 15+ children; two victims later died by suicide.

The church continues to fight against transparency in battles to unseal records, including a recent wave of 100-plus California lawsuits and a current Oregon lawsuit involving over 170 victims.

All of this is just the tip of an iceberg of similar stories that two Floodlit reporters, abuse survivors Jane and Charlie, have documented since we began investigating in late 2022.

Our public database houses more than 4,300 case reports. On a typical day, we learn of several unlisted alleged LDS abusers, and we obtain and publish more court documents regularly.

The System’s Core Issue: Risk Management Over Prevention

“When is everyone going to realize that this shit’s got to stop?” — Jane Doe

Wilson’s role itself is telling: the church handles abuse through risk management, not a dedicated prevention office. It keeps detailed records on dissenters (via the Strengthening Church Members Committee) and historical minutiae (e.g., ward minutes from 1960s Tasmania), yet claims “no ‘sexual abuse’ file.”

Why? Critics argue it’s to minimize liability, not maximize safety.

Church doctrine limits questioning, and policies like one-on-one bishop interviews (despite 2018 changes allowing observers, thanks to excommunicated advocate Sam Young) enable situations where grooming and abuse can occur.

Background checks are inconsistent, and annotations on abuser records aren’t always enforced (e.g., a convicted offender called to youth roles) – in fact, they’re sometimes erased, with First Presidency approval.

Floodlit exists to fill this void. We’ve analyzed thousands of documents and spoken with tearful survivors whose reports to bishops went nowhere – abuse continued, victims shamed.

Call to Action: Share Your Story, Demand Accountability

After 41+ years of sex abuse lawsuits, how can the Mormon church continue to claim effectiveness without data?

We invite you to help light up the system: If you reported abuse to an LDS bishop or know someone who did, share your story with us by Sept. 30, 2025.

Your experiences will inform our upcoming report on Mormon church abuse handling, to be released by year’s end.

Contact us anonymously at https://floodlit.org/report-abuse/ or email contact@floodlit.org.

Whether the bishop reported or not, we want to document it all to build a comprehensive, fact-based resource.

Thank you to survivors, advocates, and tipsters who’ve helped us expose these truths.

By gathering and publishing accurate records, we can pressure the system to change – protecting children over institutions.